Chapter 9 - The AVATAR

“We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others that in the end we become disguised to

ourselves.”

……Francois de La Rochefoucauld

This quote from de La Rochefoucauld is incredibly important in presenting this chapter. Without suggesting that all that follows could be aimed at the relationship that we have with ourselves – that is, how we see ourselves and the tools we use to define what we see – then the text from this point could be construed as meaning the therapist-client relationship. You know, the “what’s it to do with me” response.

“We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others that in the end we become disguised to

ourselves.”

……Francois de La Rochefoucauld

This quote from de La Rochefoucauld is incredibly important in presenting this chapter. Without suggesting that all that follows could be aimed at the relationship that we have with ourselves – that is, how we see ourselves and the tools we use to define what we see – then the text from this point could be construed as meaning the therapist-client relationship. You know, the “what’s it to do with me” response.

The fact is that it has everything to do with you; or maybe I should say, with both of you; - the conscious you and the subconscious you.

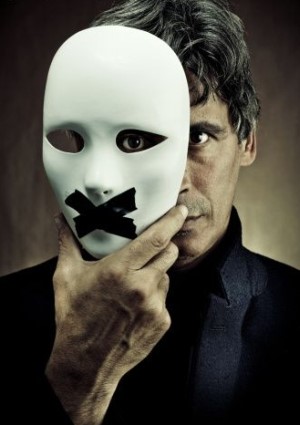

I’d like to introduce you to a character, at right, that you will hear about in this chapter. (Perhaps you have already visited this avatar-person in the "All Our Avatars" page on this site).

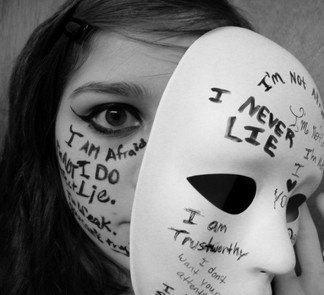

In my book, Beat Depression the Drug Free Way, and on this webpage, I address the fact that every person who attends psychotherapy, counseling, talk therapy (whatever you want to call it), in all probability, shows some sort of face to the therapist that is not his or her authentic subconscious self. In clinical affectology work, and indeed throughout this presentation, I have proposed that much of what drives us at the deepest emotional (response) level and maintains our personality, our self-beliefs, and our day-to-day existence is NON-VERBAL.

And when I say non-verbal, please accept that I mean it in its literal sense. I’ve tried to make this clear in previous chapters. The problem with ‘therapy’ (as we know it) is that in almost every case, it relies – not just heavily, but entirely – on your ability to verbalize your problems, your life, your experience of any symptoms or problems that might be ‘getting in the way of living the life you deserve’ and where it may have come from in the first place.

If we look at the clear signals and data that are offered to us by affective neuroscience, we now know that our emotional (affect) matrix and the way we set ourselves up to experience the world are laid down long before we have the ability to form words and cognitive ways of self-recognition. Depending on who and what you believe, we set up our emotional self-assessment at anywhere from 24 weeks into gestation to some time into infancy. In any case, long before what the neuroscientists call the ‘verbal emergent stage’.

Since we then have no words, yet unconsciously REMEMBER the reactions that worked in our best interests (then) and form repetitions of those reactions and quickly build habits of them at unconscious level, science shows that we become who we are – at least as an emotional being – at a time when we ‘had no words.’ This, then, attests that the building of our emotional habits are what is called “state-specific” – existing today, more or less, in the state in which they were specifically learned and cemented in our subconscious character. “State-dependent” also defines that they are existing today dependent on their non-verbal character.

So it follows that if we are reacting and forming self-assessments today out of remnants of that which is learned before words, then they defy verbal description. I hope that after all our discussions in previous chapters, you are starting to see the circular reasoning I’m applying.

The whole of the work of clinical affectology proposes that (a) much of the deeper subconscious emotional patterning that is driving mental-emotional and life problems cannot be described, analyzed, actualized, using words as the tool for reporting, and that (b) in our society, in post-Freudian times, we labor under the cultural habit of thinking we HAVE TO use words to describe our problems and the causes of our problems.

We enter the therapist’s rooms holding in front of us the face that tries to do what we believe it should do. … talk! And when we find we can’t actually delve deeply enough and ‘words fail us,’ why, then, we confabulate – try to make it up, either consciously or unintentionally.

This is why our friend in the picture above is significant to therapists, clients and online participants in the world of affectology. He represents the authentic unconscious affect person hiding behind the mask that our culture and our professions have insisted he build. The tape over the mouth represents the dynamic of clinical affectology, where the client is disallowed from talking to the extent of wandering away from the true affect subconscious self.

I’d like to introduce you to a character, at right, that you will hear about in this chapter. (Perhaps you have already visited this avatar-person in the "All Our Avatars" page on this site).

In my book, Beat Depression the Drug Free Way, and on this webpage, I address the fact that every person who attends psychotherapy, counseling, talk therapy (whatever you want to call it), in all probability, shows some sort of face to the therapist that is not his or her authentic subconscious self. In clinical affectology work, and indeed throughout this presentation, I have proposed that much of what drives us at the deepest emotional (response) level and maintains our personality, our self-beliefs, and our day-to-day existence is NON-VERBAL.

And when I say non-verbal, please accept that I mean it in its literal sense. I’ve tried to make this clear in previous chapters. The problem with ‘therapy’ (as we know it) is that in almost every case, it relies – not just heavily, but entirely – on your ability to verbalize your problems, your life, your experience of any symptoms or problems that might be ‘getting in the way of living the life you deserve’ and where it may have come from in the first place.

If we look at the clear signals and data that are offered to us by affective neuroscience, we now know that our emotional (affect) matrix and the way we set ourselves up to experience the world are laid down long before we have the ability to form words and cognitive ways of self-recognition. Depending on who and what you believe, we set up our emotional self-assessment at anywhere from 24 weeks into gestation to some time into infancy. In any case, long before what the neuroscientists call the ‘verbal emergent stage’.

Since we then have no words, yet unconsciously REMEMBER the reactions that worked in our best interests (then) and form repetitions of those reactions and quickly build habits of them at unconscious level, science shows that we become who we are – at least as an emotional being – at a time when we ‘had no words.’ This, then, attests that the building of our emotional habits are what is called “state-specific” – existing today, more or less, in the state in which they were specifically learned and cemented in our subconscious character. “State-dependent” also defines that they are existing today dependent on their non-verbal character.

So it follows that if we are reacting and forming self-assessments today out of remnants of that which is learned before words, then they defy verbal description. I hope that after all our discussions in previous chapters, you are starting to see the circular reasoning I’m applying.

The whole of the work of clinical affectology proposes that (a) much of the deeper subconscious emotional patterning that is driving mental-emotional and life problems cannot be described, analyzed, actualized, using words as the tool for reporting, and that (b) in our society, in post-Freudian times, we labor under the cultural habit of thinking we HAVE TO use words to describe our problems and the causes of our problems.

We enter the therapist’s rooms holding in front of us the face that tries to do what we believe it should do. … talk! And when we find we can’t actually delve deeply enough and ‘words fail us,’ why, then, we confabulate – try to make it up, either consciously or unintentionally.

This is why our friend in the picture above is significant to therapists, clients and online participants in the world of affectology. He represents the authentic unconscious affect person hiding behind the mask that our culture and our professions have insisted he build. The tape over the mouth represents the dynamic of clinical affectology, where the client is disallowed from talking to the extent of wandering away from the true affect subconscious self.

So, what about the relationship with yourself, and why is this story about Avatars and the like, significant if you are interested in affectology as a means of emotional resolution for you? The fact is that everything we can say about the Avatar self applies also to the way you build stories that describe yourself to yourself, and what you might bring into therapies that are based on ‘verbal revelation’ and narrative reporting. I mentioned the de La Rochefoucauld quote that led this chapter for this very reason: do not fool yourself that you have not built some way and means by which you can disguise you to yourself. And subsequently, unconsciously disguise the truth to any practitioner/therapist.

And clinical affectology is the only known approach that is created to find ways to circumvent the Avatar self and help you deal with your true affect sub-person residing at unconscious level.

Chapter Wrap-up:

_____________________________________________________________________________

And clinical affectology is the only known approach that is created to find ways to circumvent the Avatar self and help you deal with your true affect sub-person residing at unconscious level.

Chapter Wrap-up:

- Our culture, and PARTICULARLY our professional psychotherapeutic culture, has developed a deep and pervading respect for the spoken word, apparent attention to the client, and an importance on honoring autobiographical report.

- This has created a situation (in therapy) where affect is ignored, and THE WRONG PERSON is heard and attempts are made to treat that which is not your true inner self.

- Affective neuroscience research shows unequivocally that during our early life span, we become strangers to our preverbal emotional self.

- While this is true of the way that modern psychotherapeutic attitudes perform, we should not lose sight of the fact that we are far too easily fooled by ourselves and enticed to consider that what we “think about ourselves” is correct.

- This, at the expense of what we authentically feel about ourselves.

- Beware the Avatar. Even your own!

_____________________________________________________________________________

Chapter 10 - Why It All Matters

This question of “why should I care?” or “why does it matter? I’m now an adult!” is one that has chased affectology for years.

Even though Clinical Affectology began its life over three decades ago as a psychotherapy interested in helping with the reframing of emotional issues in peoples’ lives – in other words, mostly concerned with the sorts of symptoms we identify ‘therapy’ with; depression, stress, anger – the practice has become just as successful in treating people whose livelihoods depend on business decision-making and occupying a space in their minds where they operate at full potential.

It’s not so usual for those people who are operating at either less potential or downright mediocrity to realize that much of their mode of operating might be influenced by hidden preverbal governing drivers.

And just as importantly – or if you value your health, more importantly – there is less of a tendency to consider ‘emotion’ as being a quiet killer. But it can be so.

If we review Chapter 5, we can easily trace the influential action of preverbal affect initiators throughout the physical body. For many reasons to do with Western medical specialization, we have grown to be a culture that does not readily see the connection between mind and body. But consider the path.

If the deeply established affect storage system is out of balance, then this influences the way the limbic brain engages with the parasympathetic phase of the central nervous system. If the parasympathetic nervous system is out of balance, then this dynamic is transported to all organs and musculature and peripheral systems of the body. A mind out of balance means a body also out of balance.

But then, this was the crux of the text in Chapter 5, so this must serve as a revision of that text; but to focus on you and your health in a more subjective way. I include two excerpts from scholarly articles that exemplify my concern that emotions do indeed have a profound effect on our physical health and longevity.

I mentioned the idea that low-index stress (subtle level of stress that may go unnoticed – as in attitudinal stress), may play havoc with your health, even to the point of serious heart and cardiovascular disease. Here’s an important piece from the Journal of Preventive Cardiology:

Even though Clinical Affectology began its life over three decades ago as a psychotherapy interested in helping with the reframing of emotional issues in peoples’ lives – in other words, mostly concerned with the sorts of symptoms we identify ‘therapy’ with; depression, stress, anger – the practice has become just as successful in treating people whose livelihoods depend on business decision-making and occupying a space in their minds where they operate at full potential.

It’s not so usual for those people who are operating at either less potential or downright mediocrity to realize that much of their mode of operating might be influenced by hidden preverbal governing drivers.

And just as importantly – or if you value your health, more importantly – there is less of a tendency to consider ‘emotion’ as being a quiet killer. But it can be so.

If we review Chapter 5, we can easily trace the influential action of preverbal affect initiators throughout the physical body. For many reasons to do with Western medical specialization, we have grown to be a culture that does not readily see the connection between mind and body. But consider the path.

If the deeply established affect storage system is out of balance, then this influences the way the limbic brain engages with the parasympathetic phase of the central nervous system. If the parasympathetic nervous system is out of balance, then this dynamic is transported to all organs and musculature and peripheral systems of the body. A mind out of balance means a body also out of balance.

But then, this was the crux of the text in Chapter 5, so this must serve as a revision of that text; but to focus on you and your health in a more subjective way. I include two excerpts from scholarly articles that exemplify my concern that emotions do indeed have a profound effect on our physical health and longevity.

I mentioned the idea that low-index stress (subtle level of stress that may go unnoticed – as in attitudinal stress), may play havoc with your health, even to the point of serious heart and cardiovascular disease. Here’s an important piece from the Journal of Preventive Cardiology:

|

Long-term (Low-Index) Stress

Social and psychological circumstances can cause long-term stress. Continuing anxiety, insecurity, low self-esteem, social isolation and lack of control over work and home life have powerful effects on health. Such psychosocial risks accumulate during life and increase the chances of poor mental health and premature death. Long periods of anxiety and insecurity and the lack of supportive friendships are damaging in whatever area of life they arise. How do these psychosocial factors affect physical health? In emergencies, the stress response activates a cascade of stress hormones that affect the cardiovascular and immune system. Our hormones and nervous system prepare us to deal with an immediate physical threat by raising the heart rate, diverting blood to muscle and increasing anxiety and alertness. Nevertheless, turning on the biological stress response too often and for too long is likely to carry multiple costs to health. These include depression, increased susceptibility to infection, diabetes, and a harmful pattern of cholesterol and fats blood, high blood pressure and the attendant risks of heart attack and stroke. …Prof. Rajeev Gupta |

This following extract refers to attitudinal conditions as they relate to our health. It is worth noting that the sorts of attitudes that are common to high achievers (anger, perfection, superiority, even hostility) fall within the gamut of the parameters described below. This is from the Public Access files of NIH – the National Institute of Health:

|

Psychological Trait Attitudes and Health

Over the past few decades, our understanding of the health consequences of psychological factors has broadened to include both the detrimental associations of negative psychological factors (such as depression, anxiety, anger/hostility, acute and chronic stress) and the beneficial associations with positive factors, including positive affect and positive attitudes. Attitudes may affect CVD (Cardiovascular Disease) risk in several ways, by influencing an individual’s 1) adoption of health behaviors, 2) maladaptive stress responding resulting in direct alteration of physiology (i.e., autonomic dysfunction, thrombosis, arrhythmias), 3) development of traditional CVD risk factors, and 4) lack of adherence to therapy in both primary and secondary prevention. The overarching hypothesis is that attitudes, which originate in childhood and mature by early adulthood, may ultimately be responsible for a substantial portion of the burden of CVD. It is also conceivable that attitudes are important modifiable targets both for primary and secondary prevention of CVD. …NIH – National Institute of Health |

There are many such research reports available online to the public if you should care to investigate other affect and emotional psychological factors determining your path of health throughout your lifetime and right now. These are just two that point out that the knowledge most certainly does exist in Western medicine that emotion and attitudinal factors are ‘things to watch’ in our efforts to lead the good life – or I should say our efforts to lead a LONG good life!

Back to this vital question “Why should I care?”

In the title of the original eBook version of these site pages, there is the phrase, Why it Matters. And this is in reference to our ‘engine’ – that which is driving us from a deeper emotional perspective. It’s unconscious. It’s hidden. It’s the ‘ghost in the machine.’

Whether we live our lives apparently happy and content to take a middle path in achievement or we spend a lot of our time striving for perfection, making more money, rising to greater heights in the things we wish to achieve, there is a glaringly good argument for the fact that we should acknowledge that the dynamics of ‘deep emotion’ (or as we have now established within this text, ‘invisible affect’) can and DOES play a part in our health.

What greater signal can there be to start to develop a concern for ‘that which lies below’ and to take steps to balance the dynamic? Those steps? Change life-style and attitude? Maybe not. Take up meditation? Maybe. Participate in a Clinical Affectology program? Definitely.

Back to this vital question “Why should I care?”

In the title of the original eBook version of these site pages, there is the phrase, Why it Matters. And this is in reference to our ‘engine’ – that which is driving us from a deeper emotional perspective. It’s unconscious. It’s hidden. It’s the ‘ghost in the machine.’

Whether we live our lives apparently happy and content to take a middle path in achievement or we spend a lot of our time striving for perfection, making more money, rising to greater heights in the things we wish to achieve, there is a glaringly good argument for the fact that we should acknowledge that the dynamics of ‘deep emotion’ (or as we have now established within this text, ‘invisible affect’) can and DOES play a part in our health.

What greater signal can there be to start to develop a concern for ‘that which lies below’ and to take steps to balance the dynamic? Those steps? Change life-style and attitude? Maybe not. Take up meditation? Maybe. Participate in a Clinical Affectology program? Definitely.

The evolution of the brain not only overshot the needs of prehistoric man, it is the only example of evolution providing a species with an organ which it does not know how to use

….Arthur Koestler (Author: “The Ghost in the Machine”)

….Arthur Koestler (Author: “The Ghost in the Machine”)